I didn't plan to write reviews for two films by the same director in a row, but that's how it happened. Since I probably won't make it to any movies in the theater any time soon, I'm stuck with what's available on DVD. Today I watched 13 เกมสยอง, a.k.a. 13 Beloved, and now also a.k.a. 13: Game of Death, which will be released on DVD in the U.S. next month.

I didn't plan to write reviews for two films by the same director in a row, but that's how it happened. Since I probably won't make it to any movies in the theater any time soon, I'm stuck with what's available on DVD. Today I watched 13 เกมสยอง, a.k.a. 13 Beloved, and now also a.k.a. 13: Game of Death, which will be released on DVD in the U.S. next month.That's right: ชูเกียรติ ศักดิ์วีรกูล (Chukiat Sakweerakul), director of รักแห่งสยาม (The Love of Siam), knows how to do more than make audiences giggle and swoon at teenage boys locking lips. 13 Beloved is an earlier directorial effort of his, from 2006. It never managed to capture my attention before, but based on Wise Kwai putting it in his top 10 Thai films, and because I thought รักแห่งสยาม had a lot of good points, I decided to check it out.

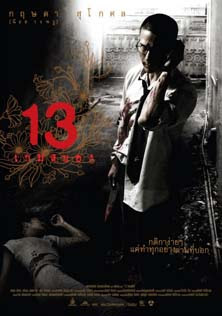

13 เกมสยอง tells the story of ภูชิต Puchit (Krissada Terrence), a band-instrument salesman who finds himself unable to keep up with increasing debt. His car is repossessed the same day an important sale goes sour, after which he finds himself out of a job with a 50,000 baht credit bill, and his mom calling to borrow money in a hurry. After getting a mysterious phone call, Puchit is forced by his dire circumstances into a sick game of 13 challenges, with the promise of a 100 million baht if he makes it to the end.

Now that I've seen two films of his, let me say this: Chukiat is another director I'm going to keep an eye on. I'm not in love with any of his work, but much like I said about รักแห่งสยาม, it's well above the average Thai film.

Amidst its more serious themes, 13 เกมสยอง has a running comic streak, and some truly hilarious moments that prove how laugh tracks and silly sound effects don't make comedy better. The scene with the "king" at the bus stop was inspired, and the scene with the Chinese family answering (er, not answering) the telephone cracked me up, too. Sometimes the film danced on the edge of the ubiquitous verbal slapstick brand of Thai comedy, but mostly it managed to restrain itself and keep me laughing. The scene in the police station is the main exception, going over the top with shouted insults like a pretty girl who doesn't know how much makeup is enough.

The effects weren't great. When it was trying too hard to act like Saw or Hostel (bloated corpse, exposed brains), it took me out of the story. Fortunately the bulk of the film's effectiveness rests upon the shoulders of its protagonist. Krissada excellently portrays the desperation of a man in the shackles of debt. The main premise serves as an apt commentary on our potential for depravity, and how we propel ourselves further down that path with each thoughtless or cruel act we commit. Sometimes we are compelled by circumstances, but in the end we must take responsibility for our own actions. I thought the film showed this conflicted part of human nature well: the clash between ideal self and actual self, and reconciling the two when a lot is on the line. This is I would never go on a show like Fear Factor. My ideal self does not do things like eat animal innards or let himself get buried alive in cockroaches, and I don't want to put myself in a situation where my actual self would even question what I consider such a basic truth about myself. (Then again, I do enjoy the occasional baggie of fried crickets from a street vendor.)

After loving the first half, the latter half was a disappointment. Half an hour in, I was saying to myself that this is a great premise worthy of a franchise. At 90 minutes, I began to wonder whether the premise could be rescued from the well it was floating in. It dragged on too long, with an unsatisfying twist. I haven't read the comic it's based on, so I can't compare the two. And I probably need to watch it again to catch the details of the ending, since I watched it without Thai subtitles. Sometimes things fly past me during inattentive moments. But the end felt squandered.

This film is not one I'd recommend to someone who had never seen a Thai movie. It suffers from some of the flaws of its numerous and terrible cousins of Thai cinema. Chukiat strikes me as a writer/director in need of a writing partner. If he can find someone to help write his screenplays, I think he could make a real masterpiece. Nonetheless, 13 เกมสยอง was good enough that I told a couple friends about it. And that says a lot.